It's no coincidence that Warren Ellis's promotion through the ranks of the Bad Seeds has dovetailed with the Indian summer that Nick Cave's long career is now enjoying.

In Ellis, Cave has finally met his match when it comes to a breadth of ambition and ferocity of workrate. In the past six years alone, they have collaborated on two Bad Seeds LPs (one a double), two Grinderman LPs, five film soundtracks, two theatre scores and toured in a full Bad Seeds line-up, a piano-based Mini Seeds quartet and as Grinderman.

Just when most rockers are settling into a middle-aged semi-retirement (Cave is 53, Ellis is 45), these two are working like men possessed. Perhaps that's the nature of addictive personalities for you.

Cave also currently seems fascinated by how quickly he can complete projects. Having spent five years labouring over his first novel, 1989's The Ass Saw The Angel, he dashed off the second, last year's The Death Of Bunny Monroe, in just six weeks during downtime while on tour, having cannibalised the ideas from a screenplay he'd written for John Hillcoat.

Grinderman seems to be another symptom of this, with all their songs written through jamming, rather than the traditional Bad Seeds format of Cave working long and hard on his ideas in his office before presenting them to the band to be fleshed out.

He first explored this way of working in the run-up to the 2004’s Abattoir Blues/ Lyre of Orpheus, gathering the nucleus of the Bad Seeds in a small studio in Paris to thrash out some ideas as part of the songwriting process before finishing them off on his own.

The departure of Blixa Bargeld from the band following 2003's underwhelming Nocturama LP may have prompted this move in an attempt to shake things up - the result was an outstanding double album to mark the start of Cave and Ellis's hot streak together.

With Grinderman, Cave seems to be trying to cut out the subsequent redrafting as much as possible and present the ideas in the rawest possible state, with most of Grinderman 2 actually managing to sound even more off the cuff than its predecessor.

What you sometimes lose in terms of the rich frame of reference in his lyrics is traded off for the sheer energy of the band thrashing about on the edge of uncertainty.

The first Grinderman LP drew heavily on the blues (the title track/band name is indebted to Memphis Slim's Grinder Man Blues) while firing it with a rough-hewn punky spirit - but Grinderman 2 finds them turning towards a greasy, blackened psychedelia.

Much has been made of Cave picking up the guitar for the first time at the age of 50 but Ellis is primarily a violinist whose guitar skills are hardly going to earn him a job running finishing classes at the Jimmy Page School of Rock.

The two of them like to combine simple overdriven rhythms with smearing great slabs of groaning and wheezing noise over the songs, some of it coaxed out of an electric mandolin, which looks like a miniature guitar and flips all the usual cock-rock posturing on its head very nicely when played live, and some from Cave on primative-sounding keyboards. Drummer Jim Sclavunos and bassist Martyn Casey provide a solid basis, including backing vocals.

Considering the back to basics ideology, the nine songs on Grinderman 2 are surprisingly wide ranging, from the bluesy howlers Mickey Mouse And The Goodbye Man and Kitchenette to the whispered minimalism of What I Know to the strange Latino groove of When My Baby Comes, with Ellis's mournful violin suddenly turning malevolent four minutes in when the whole song rises up like a vast winged creature, elbowing Cave to the sidelines in the process.

Worm Tamer returns to the midlife crisis comedy of the band's debut album, building up to the classic pay-off: 'My baby calls me the Loch Ness Monster/ Two great big humps and then I'm gone'.

Working on all those film soundtracks seems to have an impact, with opener Mickey Mouse... and Evil both coming across like the plots to old noir movies as sinister forces move in on desperate people on the run.

Heathen Child features appearances by the Wolfman, Marilyn Monroe and the Adominable Snowman, and comes with the wonderfully daft video from The Proposition/ The Road director Hillcoat (Warning: contains scenes of Jim Sclavunos's naked backside). Palaces Of Montezuma, which finds Cave back on piano and includes a carefully crafted lyric that leaves you feeling like a Bad Seeds song somehow wandered on to the wrong album, also memorably mentions a 'A custard coloured superdream of Ali McGraw and Steve McQueen' just to keep the cinematic theme going.

The vinyl version of Grinderman 2 comes with a 16-page booklet featuring lyrics (never a good thing in my book but that's for another day) and amusing graphical interpretations of the songs by Ilinca Hopfner, plus a poster of the band standing in Roman uniforms looking bored and a CD version of the album that great for the car.

Grinderman 2 is a blast from start to finish, though it's good to know we can expect a Bad Seeds album next, with all the attendant craft that involves. Cave is one of the best lyric writers out there but you have to wonder if he's in danger of spreading himself a little thin.

When the band start singing 'We are the soul survivors' on Bellringer Blues it's hard to escape the feeling that you expect a bit more than the kind of cliches Primal Scream specialise in nowadays.

But then the first person to recognise the need for a change of direction is probably Cave, so who knows what will come next.

In the meantime, the band certainly seem to be enjoying playing the songs live, with Cave still throwing himself about onstage in Manchester recently, managing to take out part of Sclavunos's drum kit three songs in, playing keyboards with his feet and even launching himself into the crowd at one point - not bad for a man who had celebrated his 53rd birthday seven days earlier.

Sunday 17 October 2010

Tuesday 12 October 2010

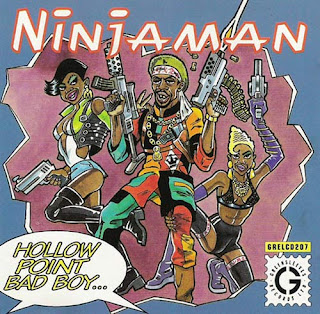

Reggae cover art

Hats off to Lars Hasvoll Bakke over at Crestock.com for his entertaining ramble through nearly 50 years of Jamaican LP cover art. Stretching across ska, rocksteady, ska and dancehall, there's much to delight, amuse and confuse in 42 Reggae Album Cover Designs: The Art & Culture of Jamaica.

Treasure Isle Dub (197?)

I spent two weeks travelling across the north coast of Jamaica in the summer of 1992, from Montego Bay to Negril and then back east to Buff Bay before heading down to Kingston on the south coast.

Dancehall was the sound of the nation back then, with Shabba Ranks the king of the hill and Buju Banton the young prince, with the reggae, rocksteady and dub that I loved seen as old hat that belonged to another generation. I did get to see Bunny Wailer and Black Uhuru play under the stars on a hill outside Montego Bay as part of Reggae Sunsplash one night, though the moths the size of bats were a little distracting.

Once I got to Kingston, I bought a stack of reggae and dub albums (I think it was from Randy's on North Parade) and lugged them all the way back to England via Freeport and Miami.

I wasn't sure which one to pick out to write about but I've gone for Treasure Isle Dub due to the cryptic sleeve that took a bit of investigation. Apart from the title of the album, the only name mentioned anywhere is in the address for 'Coxon's Music City', which is actually a mispelling of Coxsone's Music City, which would hardly have pleased Clement Seymour 'Sir Coxsone' Dodd, the legendary label owner/producer behind Studio One.

Not that Treasure Isle Dub is actually a Coxsone production - he just re-released the album and the budget clearly didn't stretch any further than a two-colour sleeve featuring the title, track listing, Coxsone's studio address and a pencil drawing of a treasure chest.

He even seems to have subsidised the whole enterprise by putting an advert for Air Jamaica in one corner on the back.

Talking of which, has Guy Hands heard about this idea? Dulux's pastel range sponsors Coldplay - he's missed a trick on that one.

Anyway, it turns out Treasure Isle Dub is a collection of rerubs of rocksteady tunes released on Duke Reid's Treasure Isle label mainly in 1966-69.

Just before his death in early 1975, Reid sold the back catalogue to Sonia Pottinger, herself a respected producer who worked with the likes of the Ethiopians, Culture, U Roy, Big Youth and Toots & The Maytals.

Pottinger handed over the tapes over to Reid's nephew Errol Brown (not the lockless Hot Chocolate frontman), who conjured up three dub albums - Treasure Dub volumes one and two, and Pleasure Dub, which has been re-released recently by Pressure Sounds.

Exactly when these albums first came out is hard to discover - my guess is 1975/76, though it could have been as late as 1979, when Brown left Treasure Isle to work for Bob Marley's Tuff Gong.

Assuming it was 1975, dub was still in its infancy back then and Brown's style is pretty straightforward, stripping the songs back and letting a few heavily reverbed vocal snippets float to the surface, while occasionally filtering guitars or drums through the echo chamber.

You race through 12 tracks in half an hour, only two of them breaking the 3-minute mark, and the mood is joyful throughout - Brown keeps you skanking all the way, rather than getting lost in a fug of studio trickery.

Considering it's a compilation (see track listing with original tunes below), it sits together very well, racing past in a blur (not something you can usually say about dub), making it tough to pick stand-out tracks. However, De Pauper A Dub is a particularly fine opener, taking Dobby Dobson's Loving Pauper to higher ground by accentuating the loping groove underpining the original while the vocal bubbles in and out of the mix.

Arabian Dub (here with a picture of the original 1970s LP cover), a rerub of John Holt's Ali Baba, is full of wet, splashing drums, cryptic vocal shards bouncing around the speakers and a great organ/guitar groove.

Dub I Love sees Alton Ellis's original vocal on Baby I Love You granted a little more respect, before being suddenly sent ricocheting around the mix, resulting in a tune that makes you want to dance around with your hands in the air.

I must confess that part of the charm of Treasure Isle Dub is the snap, crackle and pop that accompanies every track. Look close at the vinyl and it's peppered with tiny dimples and there's a curious crease in the run-out groove on side B.

It never jumps but there's quite a bit of surface noise coming off it. Had I bought it in the UK I'd probably have taken it back and asked for a new one, but having carried it halfway around the world it just adds to the charm - a fine reminder of a memorable trip.

Looking at the subsequent reissues of Treasure Isle Dub, it's interesting to see there's still confusion about who the album should be credited to, as well as the year it came out, with some (such as mine), carrying no artist name at all, some giving the honours to Errol Brown and others to The Supersonics.

Pauper A Dub (Dobby Dobson - Loving Pauper, 1967)

Construction Dub Style (John Holt & Slim Smith - Let’s Build Our Dreams, 1971)

Dub So True (Ken Parker - True True True, 1967)

Arabian Dub (John Holt - Ali Baba, 1969)

Dub I Love (Alton Ellis - Baby I Love You, 1967)

Willow Tree Dub (Alton Ellis - Willow Tree, 1968)

Touch-A-Dub (Phyllis Dillon - Don’t Touch Me Tomato, 1968)

This Yah Dub (The Sensations - Those Guys, 1968)

Everybody Dubbing (The Melodians - Everybody Brawlin, 1969)

Moody Dub (The Techniques - I’m In The Mood For Love, 1968)

Dub On Little Girl (The Melodians - Come On Little Girl, 1966)

You I’ll Dub (The Techniques - It’s You I Love, 1968)

Dancehall was the sound of the nation back then, with Shabba Ranks the king of the hill and Buju Banton the young prince, with the reggae, rocksteady and dub that I loved seen as old hat that belonged to another generation. I did get to see Bunny Wailer and Black Uhuru play under the stars on a hill outside Montego Bay as part of Reggae Sunsplash one night, though the moths the size of bats were a little distracting.

Once I got to Kingston, I bought a stack of reggae and dub albums (I think it was from Randy's on North Parade) and lugged them all the way back to England via Freeport and Miami.

I wasn't sure which one to pick out to write about but I've gone for Treasure Isle Dub due to the cryptic sleeve that took a bit of investigation. Apart from the title of the album, the only name mentioned anywhere is in the address for 'Coxon's Music City', which is actually a mispelling of Coxsone's Music City, which would hardly have pleased Clement Seymour 'Sir Coxsone' Dodd, the legendary label owner/producer behind Studio One.

Not that Treasure Isle Dub is actually a Coxsone production - he just re-released the album and the budget clearly didn't stretch any further than a two-colour sleeve featuring the title, track listing, Coxsone's studio address and a pencil drawing of a treasure chest.

He even seems to have subsidised the whole enterprise by putting an advert for Air Jamaica in one corner on the back.

Talking of which, has Guy Hands heard about this idea? Dulux's pastel range sponsors Coldplay - he's missed a trick on that one.

Anyway, it turns out Treasure Isle Dub is a collection of rerubs of rocksteady tunes released on Duke Reid's Treasure Isle label mainly in 1966-69.

Just before his death in early 1975, Reid sold the back catalogue to Sonia Pottinger, herself a respected producer who worked with the likes of the Ethiopians, Culture, U Roy, Big Youth and Toots & The Maytals.

Pottinger handed over the tapes over to Reid's nephew Errol Brown (not the lockless Hot Chocolate frontman), who conjured up three dub albums - Treasure Dub volumes one and two, and Pleasure Dub, which has been re-released recently by Pressure Sounds.

Exactly when these albums first came out is hard to discover - my guess is 1975/76, though it could have been as late as 1979, when Brown left Treasure Isle to work for Bob Marley's Tuff Gong.

Assuming it was 1975, dub was still in its infancy back then and Brown's style is pretty straightforward, stripping the songs back and letting a few heavily reverbed vocal snippets float to the surface, while occasionally filtering guitars or drums through the echo chamber.

You race through 12 tracks in half an hour, only two of them breaking the 3-minute mark, and the mood is joyful throughout - Brown keeps you skanking all the way, rather than getting lost in a fug of studio trickery.

Considering it's a compilation (see track listing with original tunes below), it sits together very well, racing past in a blur (not something you can usually say about dub), making it tough to pick stand-out tracks. However, De Pauper A Dub is a particularly fine opener, taking Dobby Dobson's Loving Pauper to higher ground by accentuating the loping groove underpining the original while the vocal bubbles in and out of the mix.

Arabian Dub (here with a picture of the original 1970s LP cover), a rerub of John Holt's Ali Baba, is full of wet, splashing drums, cryptic vocal shards bouncing around the speakers and a great organ/guitar groove.

Dub I Love sees Alton Ellis's original vocal on Baby I Love You granted a little more respect, before being suddenly sent ricocheting around the mix, resulting in a tune that makes you want to dance around with your hands in the air.

I must confess that part of the charm of Treasure Isle Dub is the snap, crackle and pop that accompanies every track. Look close at the vinyl and it's peppered with tiny dimples and there's a curious crease in the run-out groove on side B.

It never jumps but there's quite a bit of surface noise coming off it. Had I bought it in the UK I'd probably have taken it back and asked for a new one, but having carried it halfway around the world it just adds to the charm - a fine reminder of a memorable trip.

Looking at the subsequent reissues of Treasure Isle Dub, it's interesting to see there's still confusion about who the album should be credited to, as well as the year it came out, with some (such as mine), carrying no artist name at all, some giving the honours to Errol Brown and others to The Supersonics.

Pauper A Dub (Dobby Dobson - Loving Pauper, 1967)

Construction Dub Style (John Holt & Slim Smith - Let’s Build Our Dreams, 1971)

Dub So True (Ken Parker - True True True, 1967)

Arabian Dub (John Holt - Ali Baba, 1969)

Dub I Love (Alton Ellis - Baby I Love You, 1967)

Willow Tree Dub (Alton Ellis - Willow Tree, 1968)

Touch-A-Dub (Phyllis Dillon - Don’t Touch Me Tomato, 1968)

This Yah Dub (The Sensations - Those Guys, 1968)

Everybody Dubbing (The Melodians - Everybody Brawlin, 1969)

Moody Dub (The Techniques - I’m In The Mood For Love, 1968)

Dub On Little Girl (The Melodians - Come On Little Girl, 1966)

You I’ll Dub (The Techniques - It’s You I Love, 1968)

Monday 4 October 2010

Fever Ray - Fever Ray (2009)

News that Let Me In, a US remake of the 2008 film Let The Right One In, is actually pretty good and not as dismal as expected led me to dig out Fever Ray, Karin Dreijer Andersson's 2009 solo album.

I saw the original film not long after getting the album and they've become intertwined in my mind - they're both Swedish, spooky and located inside wintry domestic settings.

There's also a mutual interest in swimming pools, featuring in the videos for Andersson's When I Grow Up and If I Had A Heart and providing the setting for Eli's limb-tossing rescue of Oskar from his tormentors in the film.

Andersson even vaguely looks like an amalgamation of the two, with Oskar's straggly blond hair and Eli's mysterious, dark, rather gothic air. Seeing Fever Ray play live last year, she sang the first two songs with what seemed to be a giant insect mask on her head and subsequently spent the rest of the gig standing in the gloom near the back of the stage while lampshades flickered around her.

Andersson also likes to use pitch-shifting effects on her voice, a trick she carries over from The Knife, the band she fronts with her brother, Olof Dreijer.

Andersson also likes to use pitch-shifting effects on her voice, a trick she carries over from The Knife, the band she fronts with her brother, Olof Dreijer. She uses it to particularly good effect on album opener If I Had A Heart, with her voice sounding husky and alien as she sings the opening lines 'This will never end because I want more/Give me more, give me more, give me more' over a slowly throbbing electro backing in a manner that brings to mind Eli's ageless thirst.

The film is set on a run-down concrete Swedish housing estate covered in frozen snow and it's a scene easily conjured up by Concrete Walls, with its slow, slurred chorus of 'I live between concrete walls/ In my arms she was so warm'.

The final two songs, Keep The Streets Empty For Me and Coconut, both sound big, echoey and deserted, ideal for soundtracking a walk through slow, windless snowfall under street lights. The effect is a little reminiscent of Gier Jenssen's 1994 Biosphere LP, Patashnik, which he recorded in northern Norway on the edge of the Arctic Circle.

Not that Fever Ray is all so spooky or distant, with Andersson's ability to alchemise her surroundings into something magical sounding also stretching to the most mundane of everyday occurances.

On When I Grow Up she somehow goes from singing about the escapism of 'I want to be a forester/ Run through the moss on high heels' to the remarkable verse of 'I'm very good with plants/ When my friends are away/ They let me keep the soil moist', and somehow takes you with her - you smile rather than smirk.

Seven finds her singing about riding around on her bike and talking to an old friend about love and dishwasher tablets. But my particular favourite is 'A new colour on the globe/ It goes from white to red/ A little voice in my head goes oh oh oh', which will ring a bell with any new parent whose brief moments of respite on the sofa have been shattered by a wail from the baby monitor.

Fever Ray was largely recorded at home very early in the morning while Andersson was bringing up her two children, and lack of sleep is a theme that crops up several times.

On Triangle Walks, she mischievously sings 'Eats us out of house and home/ Keeping us awake, keeping us awake', but it's not the kids she's complaining about, it's the birds who feed on the berries outside her window.

Despite the demands of being a mother and the drain of not sleeping, Andersson seems determined to keep her creativity alive, which is why Fever Ray ultimately feels like an uplifting listen. I'm Not Done is a will to power, a refusal to give up what she loves.

Perhaps she felt a little like Eli at the end of Right One..., hidden away inside a trunk but tapping out 'kiss' in morse code confident that Oskar is still listening. We're fortunate that she stuck with it because Fever Ray is a fine album that feels all the more appropriate now winter's drawing closer.

The Chambers Brothers - The Time Has Come (1967)

I first bought this on tape in 1992 for a solitary dollar in a record shop sale in Freeport in the Bahamas and listening to it now still brings back memories of driving an American car with the steering wheel on the left but the traffic on the right side of the road.

It's since become one of a select band of albums I own on tape, vinyl and CD (Blondie's Parallel Lines , J Geils Band's Bloodshot, REM's Fables Of The Reconstruction and Miles Davis's Sketches Of Spain are the others that come to mind).

Having only ever heard a five-minute edit of Time Has Come Today previously, I was expecting psychedelic soul but Time... proved more of a curate's egg, filled with traces of the band's long journey from the Mississippi gospel circuit to fashionable Haight-Ashbury.

The Chambers Brothers had already been going 13 years by 1967, having started out as a gospel group when George Chambers quit the army to join forces with his brothers, Willie, Lester and Joe.

By the early 1960s they'd adapted their style to suit folk-blues crowds, with Lester being taught to play harmonica by Sonny Terry along the way. In 1965, they played at the Newport Folk Festival, scene of Bob Dylan's ill-received electric conversion that had Pete Seeger searching for his axe.

Never the types to turn down a paying gig, the Chambers Brothers were also happy playing to R&B crowds pumping out the likes of Long Tall Sally and Bony Moronie.

This approach won them a deal with LA label Vault in 1965 and, a year later, drummer Brian Keenan joined on his return from three years of schooling in London where the psychedelic scene was getting underway. As a result, the band soon threw themselves into the burgeoning US scene, sharing stages with the likes of Iron Butterfly and Quicksilver Messenger Service.

A new deal with Columbia followed and they immediately got busy in the studio in late '66, including an early single version of Time Has Come Today with what sounds like a sitar in the intro.

1967 saw the band's full emergence as black hippies, with the added multi-racial dimension of having a white drummer, which went down a storm on California's countercultural scene.

By the end of the year, Columbia were finally ready to release The Time Has Come. It climaxes with the 11-minute psychedelic blow-out of Time Has Come Today - but before that come a nine-track dash through much of the band's past.

The harmonising between the four brothers remained the bedrock of the band and is brilliantly showcased in covers of two very different songs - Curtis Mayfield's Impressions hit People Get Ready and Bacharach & David's What The World Needs Now Is Love.

They blow up a storm on Lester's I Can't Stand It, a cover of Wilson Pickett's In The Midnight Hour and the particularly fine Uptown, written by Betty Mabry, who later became Betty Davis when she briefly married Miles in 1968 and subsequently released a trio of stunning albums that I want to write about on here in the near future.

George's Please Don't Leave Me is pure barbershop quartet soul and they drop the pace right down for So Tired and Lester's Romeo And Juliet. The recurrent use of a cowbell throughout the album even seems to obliquely tip a hat to their country origins in the Deep South.

Finally the album winds itself up to the full version of Joe and Willie's Time To Come Today, with its spectacular echo-drenched 'time tunnel' section that showcases what a great drummer Keenan was. Joe certainly appears to have noticed when he detours his guitar solo into a sly take on Little Drummer Boy.

When it comes to naming the epic acid rock songs of the 60s, Iron Butterfly's In Gadda Da Vida seems to have stolen Time Has Come Today's thunder, which is harsh. It may be six minutes longer but it came out six months later (18 months if you count the original single version).

Mind you, both bands ultimately suffered the same fate of opening a lot of doors but not being able to capitalise for long while others took their ideas to the bank. The Chambers Brothers suffered from the lack of main songwriter, despite all four brothers earning writing credits on the album and Keenan supplying the excellent B-side Love Me Like The Rain.

Sly & The Family Stone and The Temptations under Norman Whitfield's guidance quickly seized the moment, while the hits dried up for the Chambers Brothers and the band split in 1972.

Various reunions followed but Keenan ended up working as a carpenter before dying of a heart attack in 1985. There's no better way to mark 25 years since his death than by giving The Time Has Come a spin.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)